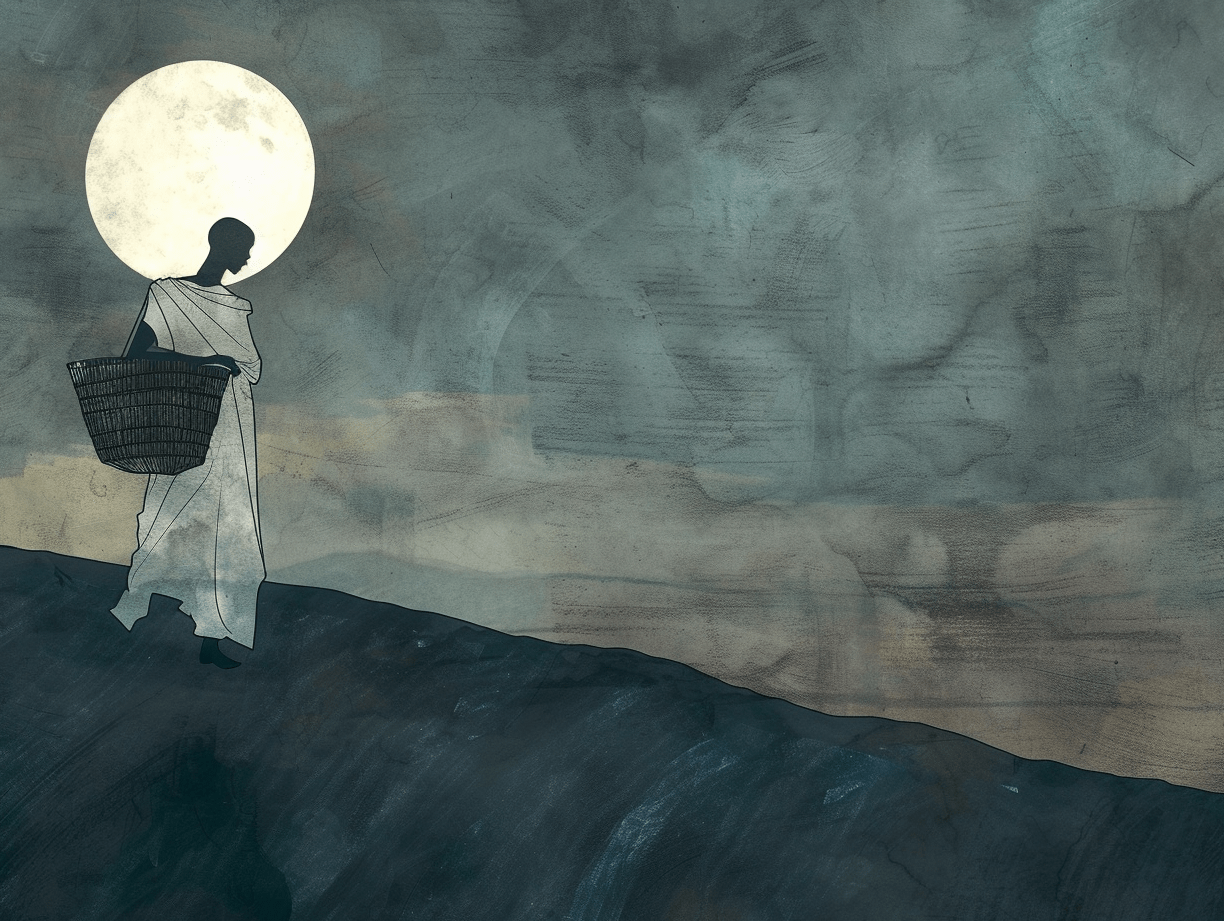

There are only dried stalks – no green herbs or hibiscus flowers – and echoes of the night owl’s hoots in the garden this harmattan night. A woman in a white wrapper stands in its middle, moving her lips in the silence. A wind blows off her scarf, revealing a shorn head that reflects the moonlight. She stirs her toes in the dusty soil, moving her feet in abandon to an unheard rhythm, holding a basket.

She goes on her knees after the owl hoots for the seventh time. She digs the soft earth with both hands and exhumes a parcel wrapped in red cloth and twine. Placing it in the basket with six others, she counts repeatedly, murmuring: “Seven, the number of beads around my waist – one for each year spent after the wedding without a child. Seven, the number of desolate farm plots at Ijesha – a wedding gift from my father for my sons.”

She rises, loosens the knot of her wrapper, drops it on the floor, and then washes her belly with cool water from an earthen pot beside her feet. Water trickles down her legs to the soil, and she chants to the winds as they journey past: ‘àgàn mi ti parí, àgàn mi ti parí, àgàn mi ti parí.’ She smiles as she chants that the days of shame and despair are over, her body will carry her baby, and he will be born before the rainy season ends.